Emergency Strategy - How to treat flail chest

Emergency Strategy - How to treat flail chest

The initial step of treatment include assessment of the airway, breathing, circulation and disability. Next the patient is position with the injured side down to stabilize the chest wall and improve ventilation in case of non injured hemothorax. In severe cases of trauma to the thorax that present with pulmonary disease, patient is admitted urgently to the emergency department.

Patient may need to be resuscitated. Adequate oxygenation and ventilation are required. Continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation and respiratory rates are performed. Oxygen administration via face mask is considered in alert and conscious patient. Continuous positive airway pressure via face mask is given to patient if he cannot maintain the partial pressure of oxygen more than 80mmHg despite high flow of oxygen. Other alternative include nasal bilevel positive airway pressure. If the above intervention fail consider mechanical ventilation or endotracheal intubation that act as physiologic internal fixation of the flail segment. Always remember the danger of pneumothorax and pulmonary contusion. Endotracheal intubation may be required in cases of respiratory failure, significant underlying disease of the lung and severe hypoxemia ( partial pressure less than 60mmHg and on room air less than 80mmHg despite 100% of oxygen). Cardiac monitoring, IV lines and pulse oximetry. The need for IV crystalloid in cases of pulmonary contusion need to be weight against the risk of developing interstitial pulmonary edema)

Pain control with pain reliever and analgesic is required to improve adequate pulmonary function and preventing atelectasis, splinting and pneumonia. Pain relief may be provided with intercostal nerve block with 0.5% of bupivacaine. It provide pain relief for 6- 8 hours. Intercostal nerve block is performed 2- 3 fingerbreadth posteriorly from the midline of the vertebrae. 0.5 ml - 1ml of 0.5% of bupivacaine is considered to be injected under the inferior surface of the rib. ( the location of neurovascular bundle).Aspiration is performed to confirm that intercostal vessel has not being damaged. The procedure ended with prophylactic antibiotic given. Narcotic analgesic/acetaminophen is also given in limited dose due to hepatotoxicity effect. NSAIDS are avoided due to gastrointestinal bleeding and if patient develop over sedation , intractable pain or hypoventilation thoracic epidural analgesic is considered.

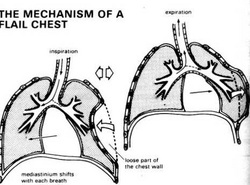

Patient with flail chest should be monitored closely in intensive care unit. Pain control is vital. The onset of flail chest may be sudden , insidious and increasing with severity with times. The symptoms and signs are dyspnea, localized pleuritic chest wall pain that is worst with coughing and respiration/deep inspiration and movement. On inspection, the flail chest will move outward during expiration and move inward with inspiration. These condition can be seen by inspecting under tangential light. Splinting respiration and muscle spasm may make it difficult to be seen.

Patient may be hypotensive , cyanosis and tachycardia. Normal breath sound will progress into wet rales or absent of the breath sounds.

Patient may present with multiple rib fractures ( crepitus, ecchymosis and bony step - off). Any erythema or tenderness on examination is associated with dyspnea, intercostal muscle spasm, splinting respiration and tachypnea.

Common disorders with similar characteristic as flail chest are dislocation or fracture of the sternum, separation of costochondrium, acute respiratory distress, congestive cardiac failure, pulmonary embolism, intercostal muscle strain, non cardiogenic causes of pulmonary edema, contusion of the chest wall, pulmonary infarction, pneumonia, pulmonary laceration and abscess.

The investigations require include full blood count, urea and electrolytes, arterial blood gases, ESR, CRP, chest radiography and CT scan. Arterial blood gases may reveal hypoxemia and raised in alveolar - arterial gradient. Chest radiography may reveal frank consolidation or patchy infiltration of the alveolar ( signs of pulmonary contusion that develop 6- 12 hours ). Chest radiography may reveal other signs such as widening of the silhouette of the mediastinum, pneumomediastinum, hemothorax and pneumothorax. Thoracic CT scan is considered as it is able to detect the rib fractures and other intrathoracic injuries that remain undetected with chest radiography.

What is flail chest ? Flail chest is a free floating segment of the chest wall. The common causes of flail chest are assault, blunt trauma, injury to the lung parenchyma adjacent to the point of impact ( development of pulmonary contusion, disruption of the alveolocapillary membrane, ventilation- perfusion mismatch, shunting of the arteriovenous and hypoxemia as well as respiratory failure which develop later, accident to the motor vehicle, missile injury ( ribs are mostly fracture at point of impact where ribs 4- 9 are common or posterior angle/60 degree rotation of the sternum. The free floating chest wall ( flail chest), may occur at the same time with separation of costochondrium, fracture of the sternum and fracture of the ribs. Pulmonary contusion is usually associated with flail chest. Usually 3 or more ribs will fracture in 2 or more places. Free floating chest wall doesn’t really affect the ventilatory mechanism. Common in elderly. Complicated by osteoporosis. It is rare in children due to elastic chest chest wall.

References

1.Pettiford, Brian L., James D. Luketich, and Rodney J. Landreneau. “The Management of Flail Chest.” Thoracic Surgery Clinics 17, no. 1 (February 2007): 25–33. doi:10.1016/j.thorsurg.2007.02.005.

2.Richardson, J D, L Adams, and L M Flint. “Selective Management of Flail Chest and Pulmonary Contusion.” Annals of Surgery 196, no. 4 (October 1982): 481–487.

3.Trinkle, J. Kent, J. David Richardson, Jerry L. Franz, Frederick L. Grover, Kit V. Arom, and Fritz M.G. Holmstrom. “Management of Flail Chest Without Mechanical Ventilation.” The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 19, no. 4 (April 1975): 355–363. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(10)64034-9.

4.Ahmed, Zahoor, and Zahoor Mohyuddin. “Management of Flail Chest Injury: Internal Fixation Versus Endotracheal Intubation and Ventilation.” The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 110, no. 6 (December 1995): 1676–1680. doi:10.1016/S0022-5223(95)70030-7.

The initial step of treatment include assessment of the airway, breathing, circulation and disability. Next the patient is position with the injured side down to stabilize the chest wall and improve ventilation in case of non injured hemothorax. In severe cases of trauma to the thorax that present with pulmonary disease, patient is admitted urgently to the emergency department.

Patient may need to be resuscitated. Adequate oxygenation and ventilation are required. Continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation and respiratory rates are performed. Oxygen administration via face mask is considered in alert and conscious patient. Continuous positive airway pressure via face mask is given to patient if he cannot maintain the partial pressure of oxygen more than 80mmHg despite high flow of oxygen. Other alternative include nasal bilevel positive airway pressure. If the above intervention fail consider mechanical ventilation or endotracheal intubation that act as physiologic internal fixation of the flail segment. Always remember the danger of pneumothorax and pulmonary contusion. Endotracheal intubation may be required in cases of respiratory failure, significant underlying disease of the lung and severe hypoxemia ( partial pressure less than 60mmHg and on room air less than 80mmHg despite 100% of oxygen). Cardiac monitoring, IV lines and pulse oximetry. The need for IV crystalloid in cases of pulmonary contusion need to be weight against the risk of developing interstitial pulmonary edema)

Pain control with pain reliever and analgesic is required to improve adequate pulmonary function and preventing atelectasis, splinting and pneumonia. Pain relief may be provided with intercostal nerve block with 0.5% of bupivacaine. It provide pain relief for 6- 8 hours. Intercostal nerve block is performed 2- 3 fingerbreadth posteriorly from the midline of the vertebrae. 0.5 ml - 1ml of 0.5% of bupivacaine is considered to be injected under the inferior surface of the rib. ( the location of neurovascular bundle).Aspiration is performed to confirm that intercostal vessel has not being damaged. The procedure ended with prophylactic antibiotic given. Narcotic analgesic/acetaminophen is also given in limited dose due to hepatotoxicity effect. NSAIDS are avoided due to gastrointestinal bleeding and if patient develop over sedation , intractable pain or hypoventilation thoracic epidural analgesic is considered.

Patient with flail chest should be monitored closely in intensive care unit. Pain control is vital. The onset of flail chest may be sudden , insidious and increasing with severity with times. The symptoms and signs are dyspnea, localized pleuritic chest wall pain that is worst with coughing and respiration/deep inspiration and movement. On inspection, the flail chest will move outward during expiration and move inward with inspiration. These condition can be seen by inspecting under tangential light. Splinting respiration and muscle spasm may make it difficult to be seen.

Patient may be hypotensive , cyanosis and tachycardia. Normal breath sound will progress into wet rales or absent of the breath sounds.

Patient may present with multiple rib fractures ( crepitus, ecchymosis and bony step - off). Any erythema or tenderness on examination is associated with dyspnea, intercostal muscle spasm, splinting respiration and tachypnea.

Common disorders with similar characteristic as flail chest are dislocation or fracture of the sternum, separation of costochondrium, acute respiratory distress, congestive cardiac failure, pulmonary embolism, intercostal muscle strain, non cardiogenic causes of pulmonary edema, contusion of the chest wall, pulmonary infarction, pneumonia, pulmonary laceration and abscess.

The investigations require include full blood count, urea and electrolytes, arterial blood gases, ESR, CRP, chest radiography and CT scan. Arterial blood gases may reveal hypoxemia and raised in alveolar - arterial gradient. Chest radiography may reveal frank consolidation or patchy infiltration of the alveolar ( signs of pulmonary contusion that develop 6- 12 hours ). Chest radiography may reveal other signs such as widening of the silhouette of the mediastinum, pneumomediastinum, hemothorax and pneumothorax. Thoracic CT scan is considered as it is able to detect the rib fractures and other intrathoracic injuries that remain undetected with chest radiography.

What is flail chest ? Flail chest is a free floating segment of the chest wall. The common causes of flail chest are assault, blunt trauma, injury to the lung parenchyma adjacent to the point of impact ( development of pulmonary contusion, disruption of the alveolocapillary membrane, ventilation- perfusion mismatch, shunting of the arteriovenous and hypoxemia as well as respiratory failure which develop later, accident to the motor vehicle, missile injury ( ribs are mostly fracture at point of impact where ribs 4- 9 are common or posterior angle/60 degree rotation of the sternum. The free floating chest wall ( flail chest), may occur at the same time with separation of costochondrium, fracture of the sternum and fracture of the ribs. Pulmonary contusion is usually associated with flail chest. Usually 3 or more ribs will fracture in 2 or more places. Free floating chest wall doesn’t really affect the ventilatory mechanism. Common in elderly. Complicated by osteoporosis. It is rare in children due to elastic chest chest wall.

References

1.Pettiford, Brian L., James D. Luketich, and Rodney J. Landreneau. “The Management of Flail Chest.” Thoracic Surgery Clinics 17, no. 1 (February 2007): 25–33. doi:10.1016/j.thorsurg.2007.02.005.

2.Richardson, J D, L Adams, and L M Flint. “Selective Management of Flail Chest and Pulmonary Contusion.” Annals of Surgery 196, no. 4 (October 1982): 481–487.

3.Trinkle, J. Kent, J. David Richardson, Jerry L. Franz, Frederick L. Grover, Kit V. Arom, and Fritz M.G. Holmstrom. “Management of Flail Chest Without Mechanical Ventilation.” The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 19, no. 4 (April 1975): 355–363. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(10)64034-9.

4.Ahmed, Zahoor, and Zahoor Mohyuddin. “Management of Flail Chest Injury: Internal Fixation Versus Endotracheal Intubation and Ventilation.” The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 110, no. 6 (December 1995): 1676–1680. doi:10.1016/S0022-5223(95)70030-7.